This tutorial has an accompanying video tutorial:

Data Structures

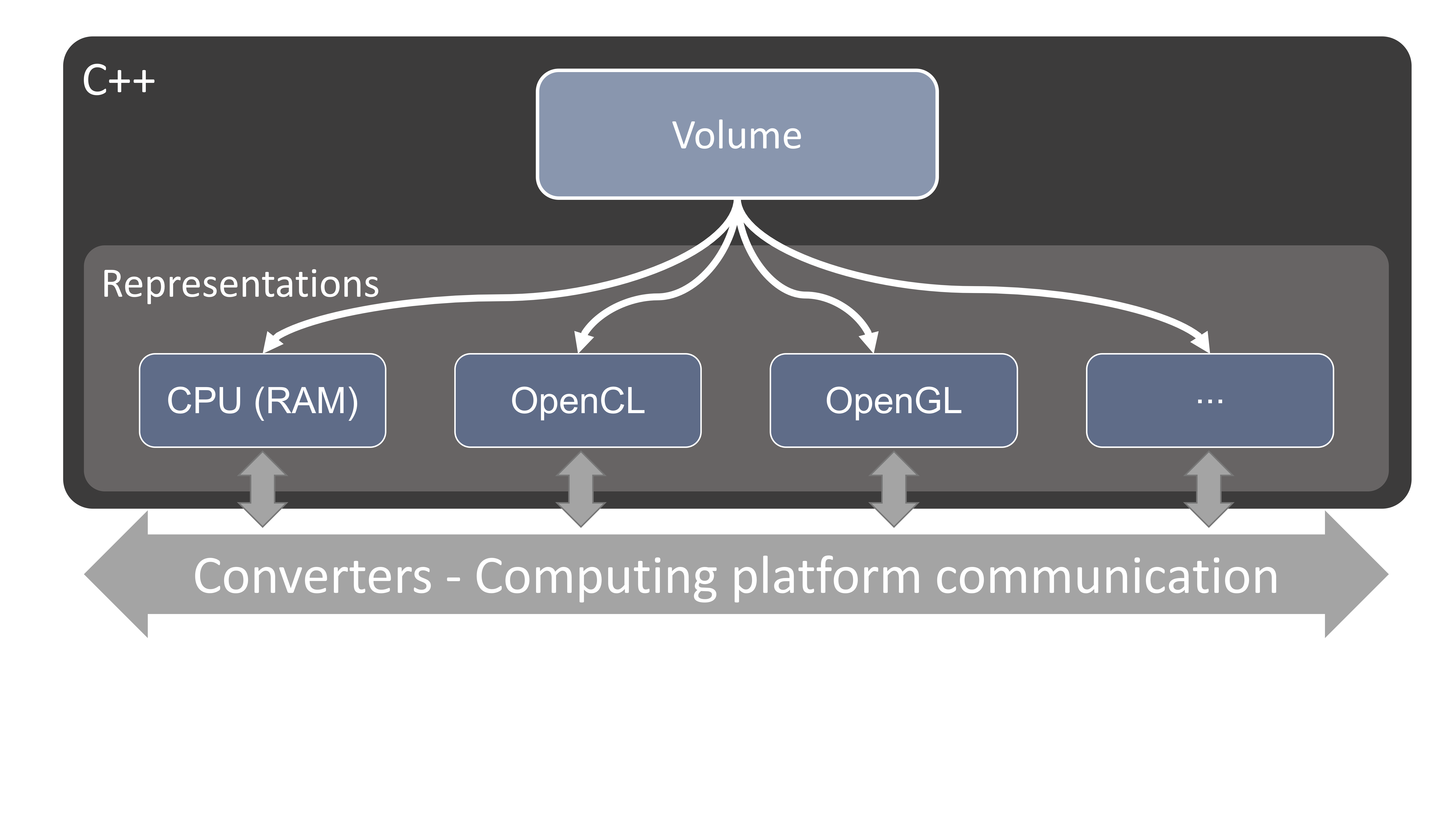

In Inviwo the main core data structures (Volume, Layer, Buffer) use a pattern of handles and representations. Note that there also exists the Image and Mesh data structure which are containers of Layers and Buffers respectively. The volume data structure for example has a handle class called Volume. The handle class by itself does not have any data, it only stores metadata, and a list of representations. The representations is where the actual data is stored. Therefore, an Image or Mesh representation is a container for Layer and Buffer representations of the same representation type. The following first explains the basic data structures and how they relate, then shows what different representations exist and how to use them.

The different structures

In Inviwo, the Volume class wraps volumetric data, more specifically data in a 3D structured grid, also with possibly multiple channels.

The Image class consists of a set of Layers, usually a color layer (what we would regularly think of as an image), a depth layer and a picking layer.

As an effect, most Image ports in Inviwo actually transfer multiple images in the conventional sense. In this example the Image would contain a Vec3UInt8 color layer, a Float32 depth layer and a UInt8 picking layer. Of course you can add more layers to the images in your custom processors as necessary.

What is a picking layer?

The picking layer basically encodes object instance IDs in color, so that a lookup in the picking layer gives the object ID for the pixel of interest. This is used for example to drag’n’drop objects in 3D space.

The third big data structure in Inviwo is the Mesh which consists of a set of Buffers. A Buffer is basically a wrapper for some linearly stored data and the Mesh holds a list of index buffers and data buffers, such as vertex positions, normals, colors etc.

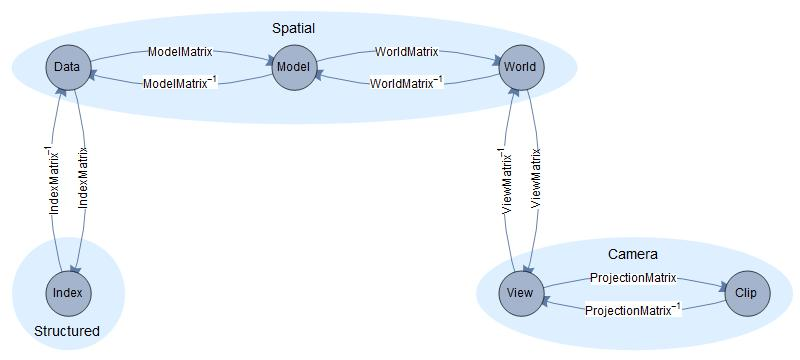

Spaces and Transforms

We name transformations according to: fromSpace To destinationSpace, i.e modelToWorld.

| Space | Description | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Data | raw data numbers | generally (-inf, inf), ([0,1] for textures) |

| Model | model space coordinates | (data min, data max) |

| World | world space coordinates | (-inf, inf) |

| View | view space coordinates | (-inf, inf) |

| Clip | clip space coordinates | [-1,1] |

| Index | voxel index coordinates | [0, number of voxels) |

Memory Representations

Any data structure can have a set of different representations, for example a Volume has a VolumeRAM representation and a VolumeGL representation. The representation basically determines where the data actually is. In general there are representations for Disk, RAM, GL and if needed also CL, where the latter refer to OpenGL and OpenCL representations respectively.

At any time at least one of the representations should be in a valid state. Whenever we want to access the data of a volume we will ask the Volume for a representation of some kind, and the handle is then responsible to try and provide that to us. If the requested representation is valid the handle can just return that representation. Otherwise, it will have to find a valid representation and try to either create the desired representation from that or convert it. (More on conversions below)

When asking a data handle for a representation, you can either ask for a read-only representation using getRepresentation<>() or for an editable representation using getEditableRepresentation<>(). Note that editing a representation invalidates all other representations in the handle, since they have not received the updates and are thus out of sync.

Conversion between Representations

Instead of specifying all representations directly for all objects, you can define a RepresentationConverter, which can then automatically convert between two representations.

For example a typical use case can be that we start with a Volume handle with a VolumeDisk representation and we want to do raycasting using OpenGL. In our processor we will then ask the Volume for a VolumeGL representation. The volume will see that there are currently no such representations. It will then try and find a chain of RepresentationConverters to create that representation. In this case that might be a VolumeDisk2RAMConverter that will read in the file from Disk into RAM, and a VolumeRAM2GLConverter that will upload the data to the graphics card. The data handle will always try and find the shortest chain of converters. I.e. if there was a VolumeDisk2GLConverter that one would have been used instead.

Example: Accessing the data in C++

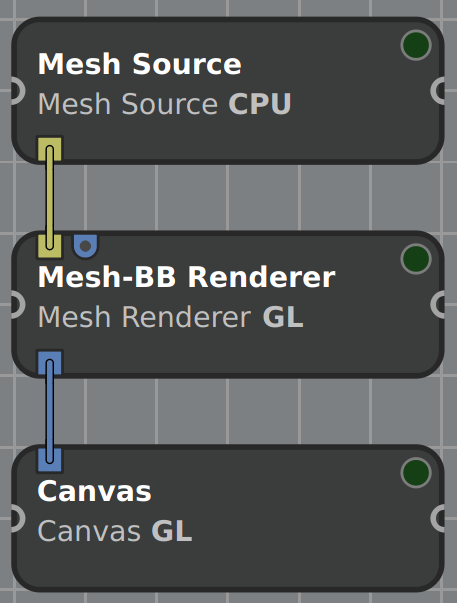

Now that we know how to get the desired representations, let’s see how to safely access the data within using the dispatch concept. We will look at rendering a mesh with its bounding box as an example.

Starting in the Mesh Source, we load a Mesh from disk, thus our Mesh handle is initialized with a set of buffers, each containing a BufferRAM representation. Note that Mesh (and Buffer) have no DiskRepresentation, while there exist DiskRepresentations for Volume, Image and Layer. However only some readers can actually load a DiskRepresentation, depending on how the data is stored on disk. The idea of the DiskRepresentation is to only load metadata and to be able to load data into memory partially later to save memory. Some data formats need the whole file to be loaded to memory in order to access all metadata, in which case the loader directly uses a RAMRepresentation.

The Mesh is passed on to the next processor with the RAMRepresentations attached. The Mesh-BB Renderer shall be a modified Mesh Renderer that also computes the meshes bounding box on CPU and takes care of rendering it. We will only look in detail at the bounding box computation and in particular how the vertex data is accessed.

In the Mesh-BB Renderer processor, the first thing we do is computing the bounding box. As a first step, we will retrieve the appropriate BufferRAM representation from the MeshInport named meshInport_:

std::shared_ptr<const Mesh> mesh = meshInport_.getData(); // Get Mesh handle

auto buf = mesh->getBuffer(BufferType::PositionAttrib); // Get position buffer

// If buffer exists and is not empty

if (buf != nullptr && buf->second->getSize() > 0) {

const auto minmax = buf->second // Get actual pointer to buffer

->getRepresentation<BufferRAM>() // Get RAM representation

->dispatch<std::pair<dvec4, dvec4>>( // Dispatch to produce a pair of vec4s

[](auto br) { // Define the lambda for all ValueTypes

// br's type in this example: BufferRAMPrecision<ValueType, BufferTarget::Data>

// which means it holds values of type ValueType and is a Data buffer

// ValueType can be extracted from br's complex type like so:

using ValueType = util::PrecisionValueType<decltype(br)>;

const auto &data = br->getDataContainer(); // std::vector<ValueType>&

// Construct result as pair of ValueTypes

using Res = std::pair<ValueType, ValueType>;

// Initialize result with max and min values of given data type

Res minmax{DataFormat<ValueType>::max(),

DataFormat<ValueType>::lowest()};

// Iterate over buffer, accumulating the min and max components

minmax = std::accumulate(data.begin(), data.end(), minmax,

[](const Res &mm, const ValueType &v) -> Res {

// Take component-wise min and max

return {glm::min(mm.first, v), glm::max(mm.second, v)};

});

// Return pair of dvec4, as we specified in dispatch's type parameter

return std::pair<dvec4, dvec4>{

util::glm_convert<dvec4>(minmax.first),

util::glm_convert<dvec4>(minmax.second)};

});

// minmax now has the lower left and upper right of the meshes bounding box.

}

We start as expected: first the Mesh handle is retrieved, then we find the buffer of interest, which is the vertex position buffer in our case. If this buffer exists, we will request its BufferRAM representation. Since this representation already exists in an up-to-date state, it can be retrieved without any memory transfer. On this representation the dispatch<ResultType>(Lambda) function is called. The actual data access is limited to the Lambda that is passed to dispatch() and the result type must match the given type parameter. The actual computations on the data happens inside this Lambda. If any additional variables from the outside scope are required in the Lambda, they can be passed into the Lambdas scope by adding them into the brackets like so:

rep->dispatch<ResultType>( [ &varFromOutsideScope ] (auto br) { ... })

The Lambda must also take one parameter, in this case auto br, that specifies the actual data type of the elements inside the Buffer. By using auto, we have C++ define the operation for all possible ValueTypes, which is a specified list of types. This way we define the function in a type-agnostic way and it will work for all data types that are used inside Inviwo. Note however, that this also requires the function to compile for all of those types.

To get the correct data type inside of the Lambdas body we can use the following line:

using ValueType = util::PrecisionValueType<decltype(br)>

This would correspond to vec3 in our example. Calling br->getDataContainer() then gives us direct access to the data by returning a std::vector<ValueType> (std::vector<vec3> in this example).

From here we can work with the data as we are used to from C++. In this example that means first setting a start value for the bounding box, initializing it with maximimum extents. Next we iterate over the whole vector and reduce it using glm::min and glm::max which return the component-wise min or max respectively. Lastly we make sure to cast our result to the specified ReturnType (std::pair<dvec4, dvec4> here). This is a pair of double precision vec4s to make sure the computation supports precision up to double. Note that util::glm_convert casts the result from vec3s to dvec4s here, so it casts them from float to double and also adds a fourth component (defaulting to value 1).

When the bounding box is computed and the processor starts to render the mesh, it will request a MeshGL (and thus BufferGL) representation. Since that does not exist, the BufferRAM representations are converted to BufferGL representations by uploading the buffers as OpenGL buffers to the GPU. The rendering process then writes to a frame buffer, which is wrapped into an Image with different Layers, each of which has a LayerGL representation only. Since the rendered image is never needed on CPU, there will only be this representation in our example.